Jul 2013

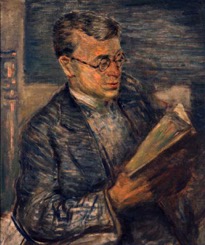

Meyer Rozenblum (ca. 1900-1942)

23 July 2013

Left: Courtesy Magnes Collection, University of California; gift of Ephraim Margolin.

Right: 1938 photograph courtesy Nelly Levin, Tel Aviv, Israel

An interesting portrait of the scholar and teacher Meyer Rozenblum by Lejzerowicz can be found in the University of California’s Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life in Berkeley. Rozenblum - called “Blum” by some of his young students in the 1930s - scratched out a meager living by teaching and tutoring. An avid chess player and Yiddish-language poet, Rozenblum was first and foremost a scholar. He was a friend of the Margolin family and belonged to their circle, having gone to school with the writer Julius Margolin. This may explain why the Margolin-Spektor family commissioned his portrait in the 1930s. In one of his books, Julius Margolin remembered Rozenblum with great affection, even though he and his friends criticized him for his passivity: “He was a complete being, faithful to his principles, incapable of compromise, hypocrisy, or lies, a free being who refused to let himself be regimented. He couldn’t belong to any party and no need would have made him accept working in an office: it would have been in contradiction with his profound self. Notwithstanding his absolutely carefree attitude, his lack of energy and ambition that was revolting to his friends, he was one of those gentle obstinate people who live by their own lights, who don’t allow themselves to be manipulated, one of those people who are the most untamed in their day-to-day humanity. . . . He led a difficult life. His activities as a teacher seemed to anguish him and to revolt him; he showed a total lack of interest in his students. But in spite of that, an atmosphere of sympathy and friendship, which he didn’t in any way foster, surrounded him. It was enough for him to just be himself: a man of an absolute independence of spirit who stood for a kind of authentically Jewish fanaticism and Innerlichkeit [introspective nature]. He annoyed us, we criticized him, . . . but we couldn’t do without him.”

Margolin reports that, having escaped from Łódź to Pinsk on the Soviet side of the border created after the German and Soviet invasions of Poland in September 1939, Rozenblum eventually decided to accept a Soviet passport and took a job in May 1940 as a French teacher in a lyceum in Krzemieniec (now Kremenets, Ukraine). After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he was murdered along with the other Jews in Kremenets in August-September 1942.

[Julius Margolin, Voyage au pays des Ze-Ka. Traduction du russe par Nina Berberova et Mina Journot, révisée et complétée par Luba Jurgenson. Paris : Le Bruit du Temps, 2010, p. 88. English translation from the French translation: William Gilcher, July 2013.]

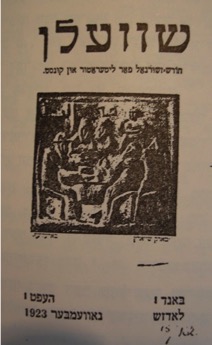

Shṿeln and other literary journals of the 1920s

11 July 2013

Left, cover of November 1923 issue of Shveln from an illustration at YIVO, New York. Right side: cover of 1924 issue, courtesy Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division, PJ5120 .A359

Lejzerowicz reportedly submitted drawings to newspapers and literary journals in Łódź in the 1920s. These covers come from issues of Shveln (which means “Threshholds”) dated 1923 and 1924. The cover on the left features an illustration by the artist Marek Szwarc, originally from Zgiersk, a town just north of Łódź, who was by then living in Paris. Alas, only the cover seems to have survived.

The issue on the right survives at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, but contains no illustrations - and also no poetry or other work by Lejzerowicz. Perhaps additional issues have survived in other collections. If anyone knows of their whereabouts, please let us know!

The literary critic Chaim Leib Fox gives the following list of Yiddish-language publications to which Lejzerowicz submitted work:

1922-23: Toyz Royt / טויז רויט

1923: Vegn / וועגן

1924-25: Shveln / שוועלן

1924-25 der fraytik / דער פֿרײַטיק

1923-1939 nayer volksblat / נײַער פֿאָלקסבלאַט

Late 1920s: lodzher togeblat / לאָדזשער טאָגעבלאַט

1926-27: ekstrablat / עקסטראַבלאַט

Working from Photographs

10 July 2013

Courtesy state archives, Łódź, 40_1381_10

Courtesy Ghetto Fighters House, Israel, image 1495

It was not possible to paint or draw openly in the streets of the Ghetto of Łódź. Therefore, like other artists, Lejzerowicz based many of his drawings on photographs. There are a number of examples of this in drawings at Yad Vashem and the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw.

The example above is more complicated. The image at the top shows Lejzerowicz at work on a major painting, “Chaim Rumkowski in the Ghetto of Lodz,” which has survived in the Jewish Historical Institute. The lower photograph shows Lejzerowicz near the bridge at the church square (Plac Kościelny). The angle of the bridge in the painting is precisely that shown in the photograph. The artist used the photograph to guide his work. Both photographs are likely the work of Mendel Grosman, who worked for the ghetto’s Statistical Department.

In documenting life in the ghetto, Lejzerowicz seems to have used many photographs by Grosman, who, according to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, had studied painting with Hirsch Szylis (another painter active in the ghetto) before becoming a photographer. Privately, Grosman documented daily life in the ghetto while also serving as one of the ghetto administration’s official photographers. Hundreds of these photographs have survived in the state archives in Łódź and can be seen online at Yad Vashem photo archives. Grosman did not survive the war.

Yad Vashem photo archives 7317/924

Mendel Grosman, likely taken in the offices of the Statistical Department of the ghetto.

Another procession

08 July 2013

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USA

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USAThere are a number of examples of works in which Lejzerowicz draws processions of people. The blog entry for July 1 showed one of them.

In today’s entry, we see a group of some 18 people – men, women, and children this time – carrying a broken menorah up a mountain on a litter or plank. Presumably this illustrates the journey of the Jewish people into Babylonian exile after the destruction of the temple. Or perhaps it is the continuing struggle of the Jewish people and their leaders to hold on to their traditions and carry the practice of Judaism up the mountain of time in a hostile world. The photograph shown here is from an album created in 1938 for Dr. Ewa Spektor Margolin. A large copy of the work - perhaps an original print - is in the collection of the artist’s niece, Ruth Lewis, formerly Ruth Leiserowitz, in Maryland, USA. Yad Vashem Photo Archives has a small photographic copy that came from Sala Lejzerowicz Rozynès, the artist’s surviving sister in Lyon, France. Lejzerowicz must have considered it a significant work, as at least two family members and a close friend were presented with copies. Without further study, it is difficult to know for sure if the original work was a print, or if what survives today was derived originally from a painting.

Werner Cohen on Hilda Stern Cohen’s experience

05 July 2013

The young German-Jewish writer Hilde Stern (1924-1997) – later called Hilda Stern Cohen – was transported for Frankfurt/Main to the ghetto of Łódź in October 1941, along with her parents, maternal grandparents, and a young male friend. By chance, they found themselves living in a room at Rybna 14a, one flight of stairs down from Lejzerowicz’s apartment. The artist/poet befriended the young woman – only 17 at the time of her arrival in the ghetto – and invited her to be part of the writers’ circle that met from time to time in his studio. Later, he saved her life by convincing Chaim Rumkowski, “Eldest of the Jews in the Litzmannstadt Ghetto,” to pull her and her father out of a group of people who had volunteered to be transported out of the ghetto. Hilda survived – the only woman of the 1,200 people on that transport from Frankfurt/Main to do so. Of her family in the ghetto, Hilda was the only one to survive the war. Her experiences are recounted in two posthumous books. (For more information, see www.HildaStory.org.)

In this short podcast, her husband, Werner V. Cohen, recounts the importance of Lejzerowicz’s role in his wife’s survival.

Podcast

Sofia Finkel de Karasik talks about her painting

04 July 2013

Karasik 27 June 2013

In 1936-37, Sofia Finkel, who was born in Tepic, Mexico where her parents had emigrated in the 1920s, spent a year and a half with her relatives in Łódź, the Margolin-Spektor family, along with her mother, Adela Margolin de Finkel. Sofia’s uncle, her mother’s brother, was the writer Dr. Julius Margolin. While in Poland, Sofia’s mother arranged for Izrael Lejzerowicz to do two paintings of her young daughter. One of the paintings now hangs in Sofia Finkel de Karasik’s home in Beverly Hills, California, where this short interview was recorded in June 2013. Click above to listen.

Religious themes: Moses

03 July 2013

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USA

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USAIn his work, Lejzerowicz returns again and again to religious themes, such as in this dynamic painting, now lost, that probably depicts Moses breaking the tablets of the law after coming down from Mt. Sinai and finding the Hebrew people worshipping a golden calf. (See Exodus 32.) Since the reproduction of this painting does not include a title, I am surmising that this is the work mentioned by Oskar Rosenfeld, one of the ghetto chroniclers and an exceptionally cultured man, at home with literature and the arts as well as history. In discussing Lejzerowicz’s paintings - based on reproductions (perhaps the same photograph that is reproduced here), Rosenfeld notes: “Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law. A composition with baroque momentum, an attempt to find new ways to be liberated from the illustrative style (Doré, Abel Pann, and the German Nazarenes).”

Lejzerowicz did at least one other painting evoking Moses, this time a large work in cubist style. Of that painting, one sketch that the artist gave to his brother Szmul/Samuel in Berlin has survived.

Courtesy Ruth Lewis, formerly Ruth Leiserowitz, Maryland, USA

Courtesy Ruth Lewis, formerly Ruth Leiserowitz, Maryland, USAVisionary, symbolic, and allegorical works

01 July 2013

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USA

Courtesy Ephraim Margolin, California, USAIzrael Lejzerowicz worked in several distinct genres. By the 1930s he was well known as a portrait painter. You can find many examples of that in the galleries in this website. During the ghetto period, Lejzerowicz continued to create numerous drawings of people in the ghetto. Many of these original works are in the collections of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw and not yet online. Most of the subjects were members of the ghetto elite, although there are also some striking drawings of poor people. Drawing the elite was doubtless helpful to the artist in maintaining his good connections to the ghetto’s leadership and thereby ensuring him some protection.

But there is another current in his work starting in the 1920s: symbolic, religious, and visionary drawings. The photograph above, showing a work that has now disappeared, is dated 1937 (or, possibly, 1931). Its meaning is unclear. Is it a theater troupe? Are the two figures on the right side clowns? commedia dell’arte stock characters? or perhaps churchmen? Is it an allegorical painting? What exactly is being portrayed? Why do these people - seemingly only men - appear to be carrying or pushing a naked woman on some kind of conveyance through the streets? Does she represent desire? sexuality? What kind of procession is this? Is it a funeral? Does anyone recognize this story? If it’s an allegory, does it represent a well-known phrase? There are multiple works in similar styles in the web galleries. Your thoughts and comments are invited!