During the ghetto period, the Nazi authorities ruled the Litzmannstadt ghetto of Łódź through Chaim Rumkowski, whom they appointed “Eldest of the Jews.”

Lejzerowicz’s survival depended on his relationship with this controversial man, who decided on allocation of resources within the ghetto – subject of course to the whims of the German military authorities.

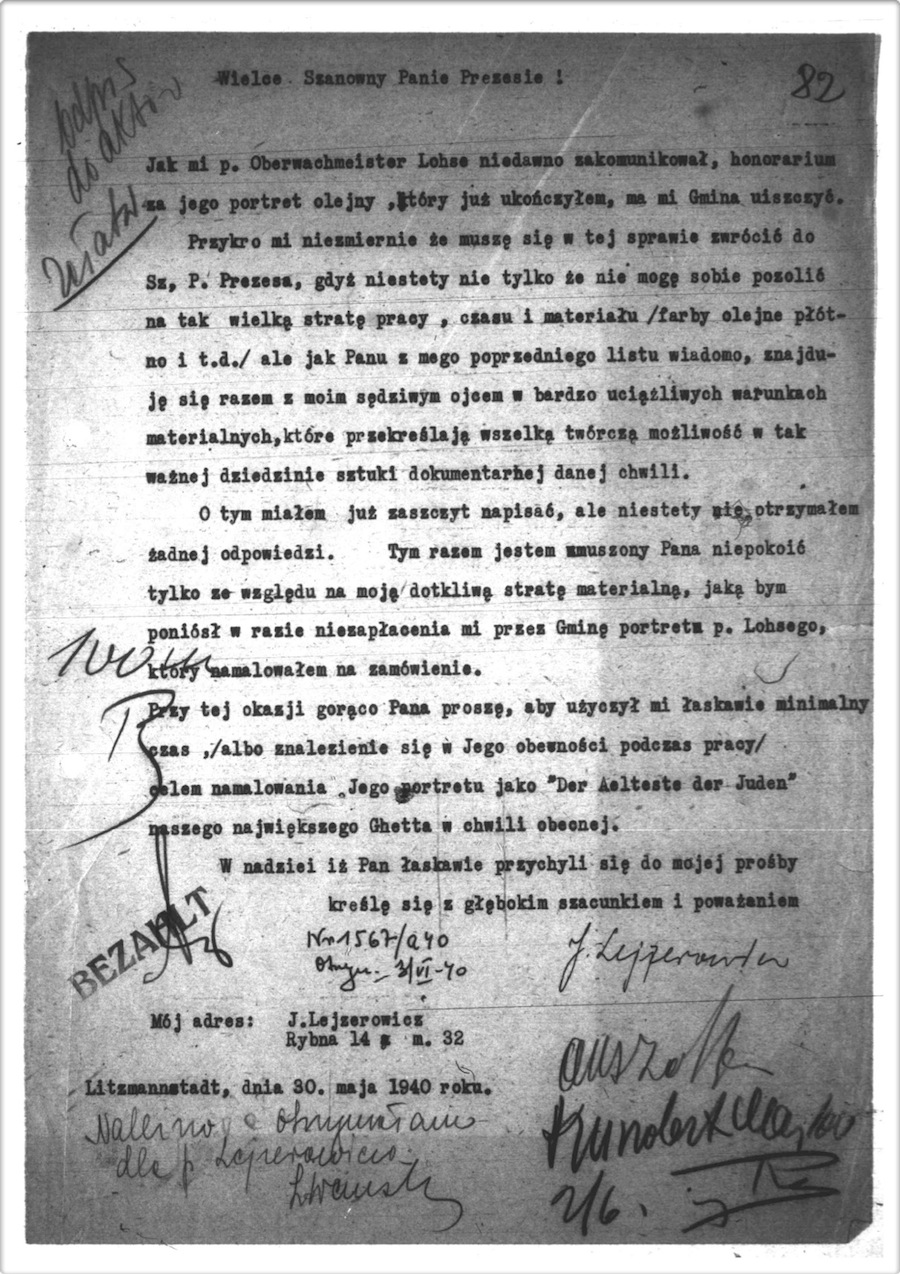

This letter, dated 30 May 1940, a few months after establishment of the ghetto itself, reveals the situation in which Lejzerowicz found himself. See below for Polish transcription, English translation, and some analysis.

Original in the Polish State Archives in Łódź:

(PL_39_278_L18901_82; made available thanks to Łódź-based historian Michał Latosinski)

POLISH TEXT:

[odpis do aktow][82]

[załatw.]

Wielce Szanowny Panie Prezesie!

Jak mi p. Oberwach[t]meister Lohse niedawno zakomunikował, honorarium za jego portret olejny, który już ukończyłem, ma mi Gmina uiszczyć.

Przykro mi niezmiernie że muszę się w tej sprawie zwrócić do Sz. P. Prezesa, gdyż niestety nie tylko że nie mogę sobie pozwolić na tak wielką stratę pracy, czasu i materiału / farby olejne płótno i t.d./ ale jak Panu z mego poprzedniego listu wiadomo, znajduję się razem z moim sędziwym ojcem w bardzo uciążliwych warunkach materialnych, które przekreślają wszelką twórczą możliwość w tak ważnej dziedzinie sztuki dokumentarnej danej chwili.

O tym miałem już zaszczyt napisać, ale niestety nie otrzymałem żadnej odpowiedzi. Tym razem jestem zmuszony Pana niepokoić tylko ze względu na moją dotkliwą stratę materialną, jaką bym poniósł w razie niezapłacenia mi przez Gminę portretu p. Lohsego, ktory namalowałem na zamówienie.

[100 m]

[R]

Przy tej okazji gorąco Pana proszę, aby użyczył mi łaskawie minimalny czas, / albo znalezienie się w Jego obewności podczas pracy / celem namalowania Jego portretu jako “Der Aelteste der Juden” naszego największego Ghetta w chwili obecnej.

W nadziei iż Pan łaskawie przychyli się do mojej prośby

kreślę się z głębokim szacunkiem i poważaniem

[Nr 1567/a40][J. Lejzerowicz]

[Otrzym. - 3/VI-40]

[BEZAHLT] [Sz(?)]

Mój adres: J. Lejzerowicz

Rybna 14a m. 32

Litzmannstadt, dnia 30. maja 1940 roku.

[Należność otrzymałam][auszahlen]

[dla p Lejzerowicza.][hundert Mark]

[L. Weinst___][2/6 R.]

ENGLISH TRANSLATION:

[copy for archive][82]

[compl.]

Right Honorable Mr. Praeses!

As Police/Guard chief [Oberwach(t)meister] Lohse informed me, the community will pay my honorarium for his oil portrait.

I am deeply sorry that I need to talk with the Right Honorable Praeses about this, but I cannot afford such a great loss of labor, time, and materials (oil paints, canvas, etc.). As you know from my previous letter, I am in a terrible material situation together with my elderly father. These bad conditions exclude the possibility of creative art so important for documenting these times.

I had the honor to write about this earlier, but unfortunately did not receive any response. This time I need to bother you again because of the severe material damage I would suffer if the community failed to pay me for Mr. Lohse’s portrait, which I painted to order.

[100 m]

[R]

On this occasion, I ask you most sincerely if you could be so kind as to offer me a little of your time (or let me be with you while you work) for the purpose of painting your portrait as “Der Aelteste der Juden” [Eldest of the Jews] of our largest ghetto in these times.

Trusting that you will graciously accede to this request

and signing with deep respect and deference

[Nr 1567/a40] [J. Lejzerowicz]

[rec’d. - 3/VI-40]

[PAID] [Sz(?)]

My address: J. Lejzerowicz

Rybna 14a apt. 32

Litzmannstadt, 30 May 1940

[I received payment] [pay]

[on behalf of Mr. Lejzerowicz.] [one hundred Marks]

L.Weinst___] [2/6 R.]

[Note: signatory is a woman]

What do we learn from this letter?

- 1. Within months of the German invasion of Poland, Lejzerowicz was desperate enough financially that he had to earn money by painting prominent Nazi officials. Lejzerowicz was able to obtain work and support from Rumkowski and the occupiers.

- 2. Lejzerowicz was living with his elderly father at Rybna 14A, apartment 32 as early as 30 May 1940, a few months after the ghetto was established and closed off. But his material conditions were desperate.

- 3. The tone of the letter shows deference to Rumkowski, yet also shows that Lejzerowicz knew he could be of continuing value to Rumkowski because Lejzerowicz was someone who could do things for the occupying forces – such as paint their portraits, a unique service that could be important. By the same token, Lejzerowicz could play off Rumkowski and the German authorities.

- 4. It is interesting that the letter is written in Polish – which brings up the issue of how languages were used in the multi-ethnic city of Łódź. Goldie Morgentaler (University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada) asks:

“I wonder why Lejzerowicz and Rumkowski would have addressed each other in Polish. Wouldn't they both have felt more comfortable with Yiddish? Was it because Polish was considered a more formal language and thus more suitable for this kind of ‘business’ letter?”

When asked by Michał Latosinski (Łódź ) about the languages used in the administration of the Litzmannstadt ghetto of Łódź, researcher/scholar Ewa Wiatr of the University of Łódź responded that at the beginning all official letters were in Polish. Later on, it was changed to German, at the order of the German occupiers, but correspondence in Polish also appears, continuing until 1944. Yiddish is rare, most often appearing in applications and requests by ghetto inhabitants. Rumkowski’s speeches, however, were in Yiddish, as he was best in this language. But Yiddish, though widely spoken in the ghetto and the most common language in the pre-war Jewish community, wasn’t usually used in Rumkowski’s correspondence. Correspondence with the Nazi administration (the Gettoverwaltung) was always in German.

Goldie Morgentaler responded to Ewa Wiatr and Michał Latosinski:

“Ewa’s answer makes sense and I did suspect that official correspondence would have been in Polish and/or German. But the language of the ghetto was surely Yiddish and it was not just Rumkowski who would have been more at ease with it. Surely Lejzerowicz would have been too. The writers’ group, after all, wrote primarily in Yiddish. And I remember something in Hilda Stern Cohen’s recollections about feeling uncomfortable at their meetings because she was using German rather than Yiddish, even though she could still be understood. I would be surprised if Lejzerowicz were not just as comfortable in Yiddish as in Polish. I worry, because it seems to me that with the precipitous decline of Yiddish in our day, people tend to forget just how widely spoken it was among eastern European Jews (and certainly Polish Jews) before the war.” - 5. The official painted by Lejzerowicz may be someone related to Hinrich Lohse (1896-1964), a prominent Nazi from Schleswig-Holstein, who a year later, in April 1941, was named Reichskommissar für das Ostland / Reich Commissar for the Eastern Territories. The Lohse mentioned in the letter told Lejzerowicz that the Jewish community would pay for the oil portrait; we don’t know if this was Lohse’s idea or actually arranged with Rumkowski’s office. Rumkowski had to accept this. The rank of “Oberwachtmeister” is not particularly distinguished; Hinrich Lohse was already a Nazi member of the German parliament in 1932, so it is possible that the subject of the painting was one of his relatives.

- 6. A woman named L. Weinstr___ was trusted enough by Lejzerowicz that she was able to pick up the money (100 Marks, a considerable sum) on his behalf. We do not yet know more about her identity. Research in the ghetto records online is inconclusive.

- 7. Lejzerowicz and Rumkowski are already talking about an official portrait of Rumkowski - perhaps one of the portraits that are shown in the series of paintings in this website.

- 8. Lejzerowicz and Rumkowski talk about his creative work as being part of the need to document the situation of the Jewish population in the ghetto. Thus, his artistic work documenting the ghetto is part of the same action that led to the work of the ghetto’s “Statistical Department” that created the chronicles of the ghetto. This was an official action of the ghetto authorities, but it also fit into the often expressed wish on the part of artists, writers, and average citizens to retain the story of what was happening to the Jewish community. It is an action of resistance to oppression.

- 9. The puppet administration of the ghetto appears to be working efficiently. Rumkowski acted quickly on this second request for payment.